Patent Terms Glossary: Your Guide To The Language of Patents

Are you new to patents? Have you encountered a specific patent term or phrase you’d like to know more about? Our helpful patent terms glossary below offers clear explanations of some of the key terms relating to patents, patent applications and other forms of intellectual property (IP).

We hope this glossary provides useful insights into the language of patents and IP, which can be complex topics. Russell IP has the expertise to help guide you through the many nuances, so please do get in touch if you need advice about a specific IP matter.

Disclaimer

Our patent terms glossary is intended to be a helpful guide for those wanting to understand some of the key terms relating to IP. While we’ve tried to ensure accuracy of the explanations given below, this glossary is for general guidance only and does not provide specific legal definitions. There are many nuances of patents that can’t be fully captured in these concise explanations.

So please don’t rely on any of these explanations as being exact definitions and please do seek advice from a patent attorney if you’re in any doubt.

Table of Contents

General terms

Intellectual property

Intellectual property (IP) is an umbrella term for a collection of legal rights which protect intellectual creations.

The four main types of intellectual property are:

- patents: protection for inventions;

- trade marks (sometimes written as “trademarks”): protection for names, logos and slogans;

- designs: protection for the appearance of products; and

- copyright: protection for creative works, such as books, music and films.

Patent

A patent is a legal right which protects an invention. The owner of a patent has the right to exclude other people from certain acts, such as making, using or selling the patented invention, in the territory or territories covered by the patent. This legal right to exclude others from doing something is sometimes referred to as a monopoly because the patent owner is the only person who can control use of the patented technology while the patent is in force.

See also: patent application.

Invention

An invention can be thought of as a product, process or method which solves a problem. An invention might be patentable if it involves a new and non-obvious combination of features or steps.

See also: inventor.

Inventor

Under UK patent law, an inventor is an “actual deviser” of an invention. Several inventors can be actual devisers of a single invention, in which case they can be known collectively as joint inventors.

Patentee

A patentee is an owner of a patent. A patent can have more than one patentee. A patentee is also referred to as a patent proprietor.

Patent application

A patent application is an application to be granted a patent for an invention. “Patent pending” (sometimes written as “patent-pending”) means that a patent application has been filed but does not mean that patent has been granted yet. Until a patent has been granted, the applicant cannot enforce their rights under the patent against anyone else.

A patent application includes formal information and a patent specification.

Formal information

A patent application’s formal information includes bibliographic details like the name and address of the applicant; the name of the inventor; and the name and address of the patent attorney or agent representing the patent applicant.

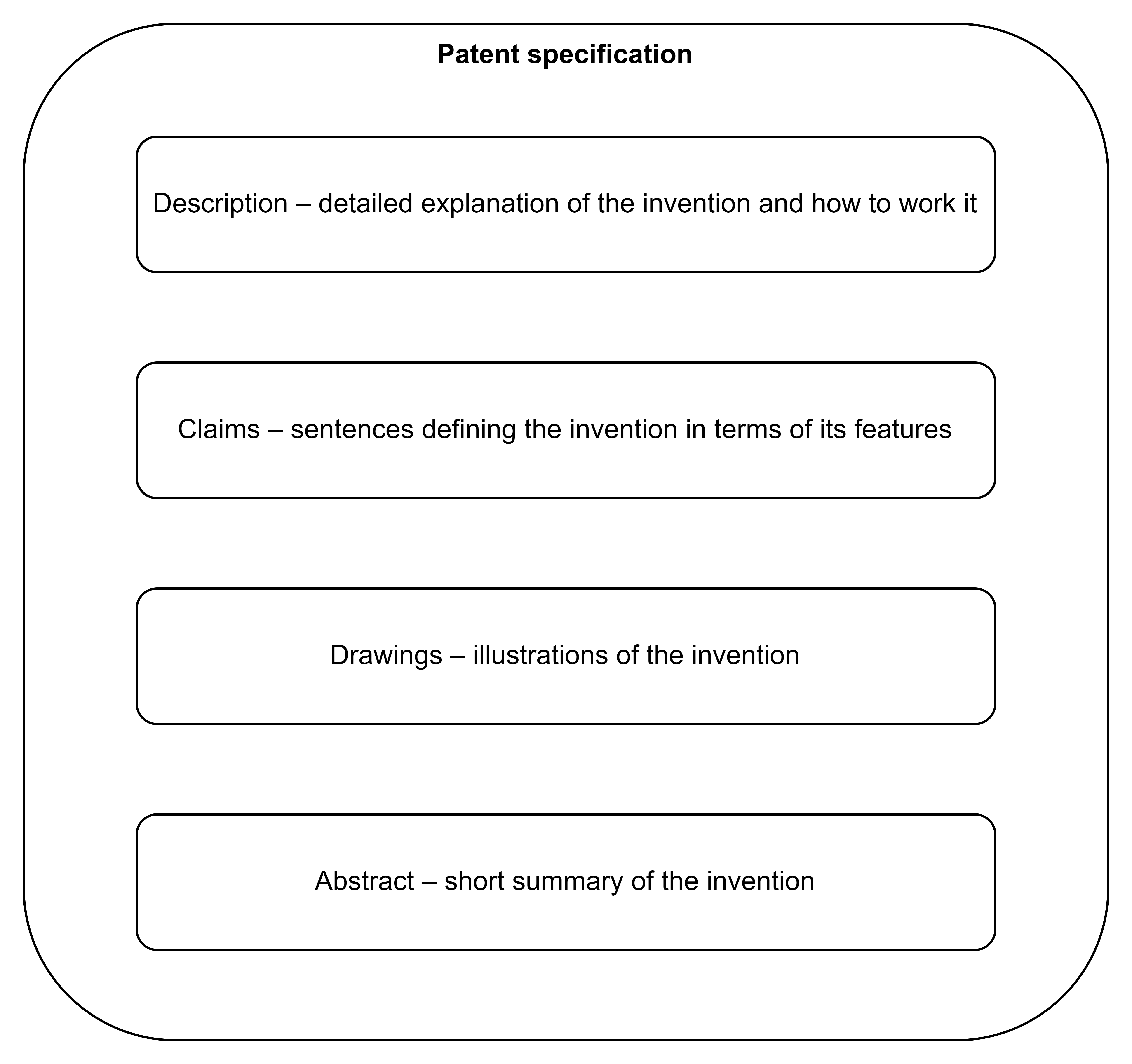

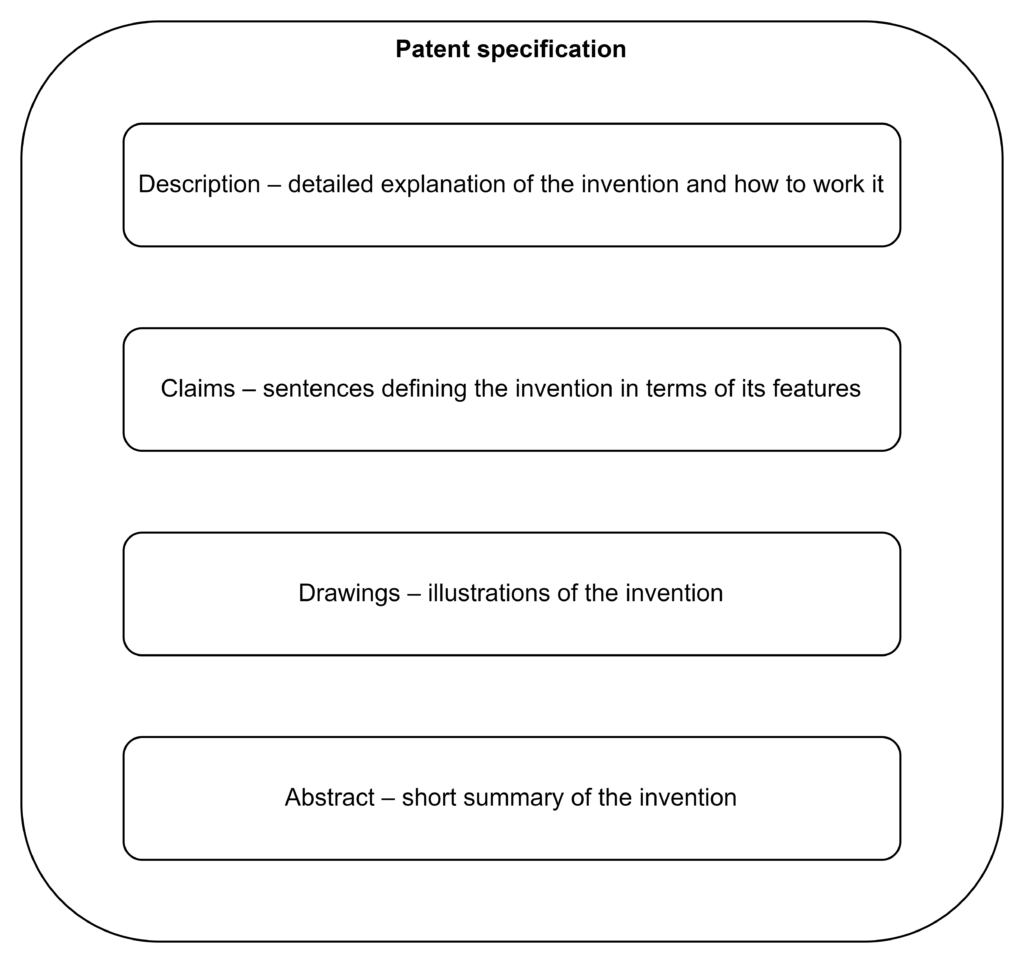

Patent specification

A patent specification (often known as a “spec” or “patent spec”) is a document which sets out the technical details of an invention. The patent specification includes:

- a description of the invention;

- claims defining the invention;

- drawings illustrating the invention; and

- an abstract providing a brief overview of the invention.

Description

The description provides an explanation of how to work the invention. The description must provide enough detail for a person skilled in the art to be able to make and operate the invention without having to invent the invention themselves. The description typically discusses several different examples or embodiments of the invention so that the reader can understand the breadth or scope of the invention. The description may also discuss the advantages, benefits and technical effects that the features of the invention provide.

Claims

A claim defines essential or optional elements or features of an invention. There are typically between 10 and 25 claims in a patent specification.

Independent claims

An “independent” claim stands on its own as a complete definition of the invention.

Dependent claims

A “dependent” claim includes the features of another specified claim or claims. For example, claim 1 may be an independent claim to a device, and claim 2 may be a dependent claim which includes all the features of the device of claim 1 plus the additional features listed in claim 2.

Drawings

The drawings (or figures) illustrate one or more embodiments of the invention. Drawings typically include reference numbers (also known as reference numerals or reference signs) identifying different elements shown in the drawings. The reference numbers are used in the description when describing the corresponding elements. The reference numbers may also feature in the claims, to help the reader interpret the claims.

Abstract

The abstract provides a short overview or summary of the invention. The abstract is intended to help readers quickly identify whether the patent or patent application is relevant to them.

Priority

Claiming priority to an earlier application (a priority application) allows a patent application to be treated as if it were filed on an earlier date (the priority date). For example, a priority application may be filed in the UK and one or more priority-claiming applications can subsequently be filed in other countries within a set time period, as if they had been filed on the same day as the UK patent application. This can stop some disclosures from being prior art for the priority-claiming application(s).

Prior art

Under UK legislation, “prior art” means “all matter (whether a product, a process, information about either, or anything else) which has at any time before the priority date of that invention been made available to the public (whether in the United Kingdom or elsewhere) by written or oral description, by use or in any other way”. In practice this means that anything that is public knowledge before the earliest effective date of the patent application is prior art for any inventions claimed in that application.

Applicant

Term of patent

The term of a patent (or patent term) is the maximum length of time the patent can remain in force. In most territories, the patent term is 20 years from the filing date of the patent application. Periodic renewal fees must normally be paid to keep the patent in force.

Different types of patent application and patent

UK patent applications

UK patent applications are processed by the UK Intellectual Property Office (UK IPO) and cover the UK. UK patent application documents must be filed in or translated into English or Welsh.

Under certain circumstances, UK patents can be extended to cover other territories, such as self-governing UK overseas territories or other jurisdictions which have historically had links to the UK. Hong Kong has a procedure for registering UK patent applications and the UK patents they become, to give protection in Hong Kong. The same procedure can also be used in conjunction with Chinese patent applications and patents, and with European patent applications and patents designating the UK.

European patent applications

European patent applications are processed by the European Patent Office (EPO) and can cover many countries, including the UK (not just the EU). European patent application documents must be filed in or translated into one of the official languages of the EPO: English, French or German. The language used will be the “language of proceedings” – the language in which the EPO will examine the application.

Claims translations

If the EPO decides that a European patent can be granted, the applicant must pay a grant and printing fee and supply translations of the claims into the two official languages of the EPO which are not the “language of proceedings” (see above). The European patent will then be published with all three versions of claims.

European patent validation

If a European patent is granted, the patentee must decide which of the countries to maintain patent protection in and “validate” the European patent in those countries. The validated patent rights become separate national or regional rights, each requiring individual enforcement and payment of separate renewal fees. Thanks to special agreements between the EPO and various other territories, European patents can also be validated in countries including Cambodia, Georgia, Moldova, Morocco and Tunisia. For more information, see the EPO’s validation pages.

Since 2023, European patentees have also had the option of obtaining a unitary patent.

Depending on the territories chosen for validation, additional translations may be required.

PCT applications

PCT applications are international patent applications. A PCT application allows the applicant to pursue patent protection in over 150 territories around the world. Eventually, a PCT application must be converted into separate national or regional patent applications which proceed independently of one another. National or regional patent applications which derive from a PCT application are referred to as “national phase” or “regional phase” applications. They are also sometimes known as “ex-PCT” applications. Before national or regional applications have been filed, the PCT application is said to be in the “international phase”.

Importantly, there is no such thing as a “PCT patent” or a “worldwide patent”; a PCT application can never become a granted patent itself.

PCT stands for Patent Cooperation Treaty. PCT applications can be received, searched and examined by many patent offices around the world, depending on the nationality and residence of the applicant(s).

Divisional applications

A divisional application is an application which is based on an earlier patent application, known as a “parent” patent application. A divisional application may only contain subject matter which was present in the earlier application. A divisional application is typically filed: (i) when the earlier application contains two or more inventions that the applicant would like to protect; (ii) if the applicant wants to try to secure a different scope of protection from that of the parent application; and/or (iii) to keep options open when a parent application is due to be granted.

The term “divisional application” means something more specific in US patent law and practice, which is outside the scope of this high-level glossary.

Unitary patents

A unitary patent is a singular patent right covering many EU countries. A unitary patent can be enforced in all the relevant countries through a single proceeding before the Unified Patent Court.

Patent offices and organisations

Patent offices or intellectual property offices receive and process patent applications. Patent offices are usually run by national governments or regional cooperatives and may grant patents covering their respective jurisdictions. Some patent offices and intellectual property offices process other types of IP applications in addition to patent applications.

UK Intellectual Property Office

The UK Intellectual Property Office (UK IPO) is the operating name of the UK Patent Office. The UK IPO receives and examines UK patent applications and grants UK patents. The UK IPO also handles trade mark and design registrations covering the UK. The UK IPO is based in Newport, Wales.

European Patent Office

The European Patent Office (EPO) receives and examines European patent applications and grants European patents. The EPO is based in Munich, Germany with offices in other locations, including The Hague, Netherlands.

World Intellectual Property Organization

The World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) is an agency of the United Nations (UN). WIPO seeks to promote intellectual property throughout the world. WIPO administers several major cooperative treaties, including the Patent Cooperation Treaty. WIPO is based in Geneva, Switzerland.

European Union Intellectual Property Office

The European Union Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO) is an agency of the EU. The EUIPO is responsible for receiving and examining applications for EU-wide IP rights including EU designs and EU trade marks. The EUIPO is based in Alicante, Spain.

The patenting process

Preparing a patent application

Preparing (or drafting) a patent application involves:

- working with the inventor(s) to understand the invention in detail;

- identifying what is new and advantageous about the invention;

- drafting a patent specification directed to the invention; and

- collecting the necessary formal information.

Drafting the patent specification may include multiple iterations, depending on the complexity of the invention.

Filing a patent application

Filing a patent application involves submitting the patent specification and the formal information to a patent office. Patent offices typically have specific forms for collecting the required formal information. For example, the UK IPO has “Form 1” which prompts the person submitting the patent application to enter most of the necessary information.

The patent specification is usually filed as a PDF file or a collection of PDF files for the different components of the specification. Other formats are becoming accepted, such as DOCX.

Once the application has been filed, the patent office will issue a filing receipt confirming the filing number and the filing date. If a UK patent application is filed online, an electronic filing receipt is usually automatically generated as soon as the filing is complete.

Publication of a patent application

A patent office will normally publish a patent application 18 months after the “effective filing date” of the application. The effective filing date may be the actual filing date of the patent application, or the earliest priority date of the patent application. This is an important part of the bargain that patent applicants enter into with the patent office: in exchange for a temporary monopoly over the invention, the applicant agrees to share details of the invention with society. This bargain is sometimes called the “quid pro quo”. Once patent protection for the invention has expired, the invention is in the public domain and no longer under the patentee’s control. Over time, this increases society’s collective knowledge and technological understanding.

Prosecuting a patent application

Prosecution is the iterative process that takes place between the patent applicant and the patent office after a patent application has been filed and before a patent is granted. Prosecution usually involves several distinct stages. The prosecution process is intended to ensure that the patent application meets the necessary requirements for grant of a patent.

Formal examination

A patent office will usually check a patent application to make sure the application has been filed correctly and is not missing any information. This process is often referred to as “formal examination”, “formality examination”, or “preliminary examination”.

If the patent office identifies any formal deficiencies in the patent application, the patent office issues a preliminary examination report. The preliminary exam report sets a deadline for the applicant to remedy the deficiencies.

Search

Depending on the jurisdiction, the patent office may conduct a search for relevant prior art. Typically a prior art search involves searching for published patent applications and patents to try to identify documents disclosing similar combinations of features to those of the invention. However, anything which was available to the public before the effective filing date of the patent application can be prior art. It is not unusual for patent examiners to cite journal articles, scientific papers, YouTube videos, blog posts, website pages and other sources as prior art.

When the search has been carried out, the patent office issues a search report listing the identified prior art. When sending the search report, the patent office might set a deadline for the applicant to reply or complete a further step, such as requesting substantive examination. The prior art documents listed in the search report are often called “citations”, “references”, or “cited documents”.

Many patent offices categorise the identified prior art in the search report based on its perceived relevance to the invention. For example, a category “X” citation is considered to be particularly relevant to the invention, whereas a category “A” citation is considered to be of background interest only.

Substantive examination

Depending on the jurisdiction, the patent office may also check that the invention defined in the claims of the patent application is new, inventive and meets the other requirements for patentability in that territory. This process is known as substantive examination. The applicant must normally request substantive examination by a specific deadline – otherwise the application may be deemed withdrawn.

A patent examiner at the patent office issues a substantive examination report (usually known as an “examination report”, “office action”, or “official communication”) setting out the examiner’s findings about whether the invention meets the requirements for patentability. The examination report sets a deadline for addressing the issues raised in the report. The applicant must respond to the examination report by the deadline or the patent application will be deemed withdrawn. It is much more common for an examination report to raise some objections than for no objections to be raised at all.

Combined search and examination

Patent offices, including the UK IPO, sometimes combine search and substantive examination together. For example, the UK IPO sometimes issues a so-called “combined search and examination report” (CSER). Similarly, the European Patent Office (EPO) sometimes issues an “extended European search report” (EESR). The EESR lists the documents the EPO has found in a search for prior art which might affect the patentability of the application. The list of documents is accompanied by a written opinion setting out why the EPO considers the listed documents to be relevant to patentability.

Replying to an examination report

Replying to an examination report typically involves identifying arguments against the examiner’s objections to the patentability of the invention and submitting a reply which makes those arguments. Sometimes that is all that is required to overcome the examiner’s objections to the application.

If the examiner has identified relevant prior art, it may be necessary to amend the claims. In such cases, the person preparing the reply must identify a new feature or different combination of features which is not disclosed in the prior art, or rendered obvious by the prior art, and add that feature combination to the claims. Claim amendments should usually be accompanied by an explanation of where the feature is disclosed in the applicant’s patent application as filed and why the claims as amended are new and inventive compared to the prior art. There are other reasons why claims might be amended in reply to an examination report, such as in response to clarity and unity objections.

A typical patent application undergoes several rounds of substantive examination before the application is granted or refused.

Grant of a patent

Notification of intention to grant a patent

If the patent office is satisfied that a patent application meets the requirements for grant of a patent, the patent office will issue a document informing the applicant of this outcome. This document is normally referred to as a notification of intention to grant a patent, a notice of allowance, or the like.

Grant formalities

The notification of intention to grant a patent issued by the patent office may set a deadline for the applicant to complete certain formalities. For example, the applicant may be required to pay a grant or publication fee, file translations of the claims or other parts of the application into other languages, or confirm that the applicant accepts the claims that have been approved for grant.

Publication of patent

When the applicant has attended to the grant formalities, the patent office will usually publish a copy of the granted patent for public inspection. The published patent allows third parties to see the protection conferred by the patent.

Renewal of a patent

In most territories, a patent must be renewed periodically to keep it in force. For example, in the UK, annual renewal fees (sometimes known as “maintenance fees”) must be paid to the UK IPO. Renewal fees typically increase in cost with the age of the patent. Patentees must therefore decide each time a renewal fee is due whether they wish to keep their patent in force. A patentee may choose to let a patent lapse if the cost of renewing the patent is not justified by the additional revenue or other commercial benefit generated by the continued existence of the patent. There can be financial incentives, such as Patent Box tax relief, to keep maintaining a patent.

In some territories, renewal fees have to be paid while the patent application is still pending and before it has been granted. This is the case with a European patent application.

Patent attorneys and other legal professionals

Patent attorneys

Patent attorneys help applicants with the patenting process. Patent attorneys typically:

- provide initial advice about whether something might be patentable;

- draft patent applications;

- file patent applications at patent offices;

- reply to formal and substantive examination reports;

- manage formal aspects of patent applications and patents, such as keeping track of deadlines and paying official fees;

- provide strategic advice about where and how to pursue patent protection in other countries; and

- instruct foreign attorneys to file and prosecute patent applications in other territories.

Patent attorneys are usually qualified to act in a specific territory or territories. For example, Russell IP’s patent attorneys can act before the UK Intellectual Property Office, the European Patent Office and the World Intellectual Property Organization. Russell IP works with patent attorneys in other territories (such as other European countries, the US, Canada, Australia, China and Japan) to help clients pursue patent protection in specific national/regional jurisdictions.

Perhaps surprisingly, patent attorneys usually have a technical background (such as a degree in maths, physics, chemistry, engineering or another STEM discipline) rather than a legal background (such as a law degree). Most patent attorneys start special legal training after they join the patent profession. For example, patent attorneys operating in the UK typically qualify as Chartered UK patent attorneys and as European patent attorneys.

Solicitors

Some solicitors specialise in intellectual property. Intellectual property solicitors tend not to prepare and file patent applications or deal directly with patent offices during prosecution of patent applications, unless they’re also patent attorneys. Intellectual property solicitors may focus more on advising patent owners on enforcing their patents against other people or businesses. These solicitors may also engage barristers or other professionals to help run court cases to enforce a patentee’s patent rights in court.

Intellectual property solicitors may also carry out other activities in relation to patents. For example, they may advise on contractual matters like non-disclosure agreements (NDAs)/confidentiality agreements and patent transactions, such as patent sales or patent licensing. They may carry out due diligence in relation to a patent transaction. This involves checking that the patents and applications one party claims to have really do exist and are in the state asserted by the party. Patent attorneys may also carry out this work.

Patent transactions

Patents and patent applications are assets, meaning they can be transacted like any other personal property. For example, patent applications and patents can be bought, sold, licensed or mortgaged by their owner. Patent transactions like these often need to be registered at the relevant patent offices.

Sale of patents

Patents can become highly valuable. Patents (and patent applications) may be sold in exchange for money or other commercial benefit. Russell IP’s founder, Iain Russell, is one of a small number of patent attorneys who has built and sold a multi-jurisdictional patent portfolio of his own inventions, relating to drone technologies.

Patent licensing

Patents (and patent applications) may be licensed by the patentee (licensor). This is usually done through a licence agreement which is entered into by the licensor and the party taking the licence (licensee). The licence agreement sets out what the licensee is allowed to do in respect of the invention, and what the licensee must give the licensor in return, e.g. pay royalties. This can be a valuable way for a patentee to generate revenue from a patent portfolio.

Important note

This patent terms glossary focuses primarily on UK and European patent practice. Other jurisdictions use different language for some of the terms identified above and have different procedures.

Last updated: 14 December 2024